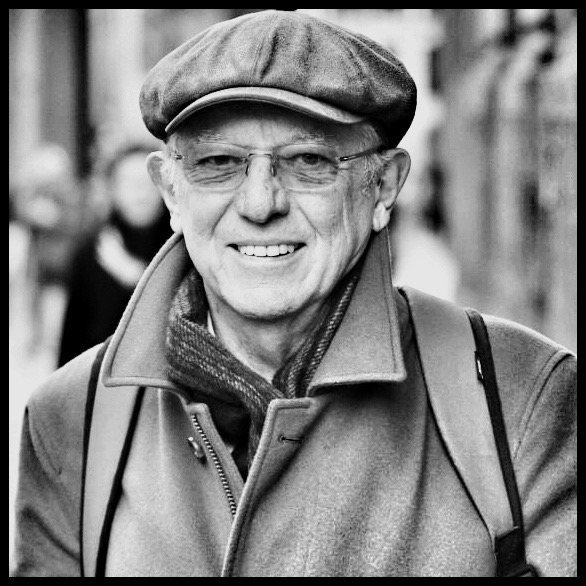

Children with special needs and their families have been hit particularly hard by restrictions put in place to manage coronavirus. We spoke to Professor Paul Gringras, a specialist in sleep and neurodisability at the Evelina London Children’s Hospital, about the challenges facing them.

Tell us a bit about the children and families you work with

We have a really busy clinical department seeing thousands of children with developmental issues such as autism, ADHD and often rare genetic syndromes. They are an incredibly complex and vulnerable group often with behavioural challenges and very disrupted sleep.

What happened during lockdown?

At our clinic we tend to see the most severely-affected children and their care involves many professionals. Ideally, sitting at the centre of all these revolving cogs is a community paediatrician, coordinating and overseeing it all. During lockdown 50% of those paediatricians were redeployed to acute services. Many children also get support from speech and language therapists, psychologists, physiotherapists. Around 80% of those professionals were redeployed. In addition to this, schools and respite services were shut down. So suddenly you are left with this complex group of children spending all of their time at home, many with parents who might be struggling with work and with their own stresses.

What was the impact on these families?

Many of these families have children whose behaviour is so challenging that they can only carry on because of school, respite care and short breaks. During lockdown that all stopped and often things deteriorated so badly that social services needed to be involved. For a lot of children with autism, a change in routine can lead to an increase in anxiety and more challenging behaviour, where they might self-injure or injure other people. Many of the children I see are asleep for only two hours in the night, so well-meaning families end up completely at the end of their tether, unable to cope.

According to a survey carried out in April by the Family Fund, a charity that supports parents of children with disability and illness, 94% of families said the health and wellbeing of their disabled or severely ill child was negatively affected during lockdown. Sixty five per cent said their access to formal support services such as physiotherapy and mental health services had declined or stopped. In addition, 30% of parent carers said they were struggling to afford food.

What lessons have been learned from the first wave of the pandemic?

During the first wave some of my colleagues were redeployed only to find themselves manning phone lines or handing out PPE. So many people volunteered from all walks of life but in fact very few volunteers were actually used. It looked good but what on earth was it for? I’m not underplaying the heroic activities of colleagues at the frontline, and those who were redeployed and did amazing work, but I don’t think we should be so quick next time to say ‘all hands on deck’. We shouldn’t become a ‘Covid NHS’ again and we really must try to ensure that the multi-disciplinary services that provide a scaffold for children with special needs are maintained.

What could be done differently with regard to schools?

Like many paediatricians, I really struggle with the idea that we live in a country that opened pubs before schools. Schools are still having to invest extra time and resources related to Covid-19, yet I believe their extra funding for this stopped in July.

Part of the problem is that it’s been left up to individual schools to interpret the government advice, so you end up with huge variability. There are amazing examples of schools going above and beyond, with teachers visiting vulnerable children at their houses during lockdown and not leaving until they had said good morning to the child, but we’ve been told about schools which effectively said, ‘Nobody’s told us how to do this so we’re not going to do it’. One of my patients is a child who is blind but goes to a mainstream school where he is taught braille, hand-over-hand. In March he was told that he shouldn’t expect to return to school any time in the next year because he wouldn’t be able to socially distance and they had no guidance on how to manage a child with visual impairment in the current circumstances.

How has Covid-19 changed the way children’s health services are delivered?

At the Evelina London, 90% of our appointments are now done virtually and I’m not sure we’ll ever return completely to the way it was before. IT innovations happened almost overnight and this echoes changes across the whole NHS, so virtual working from home is possible for most of us. However, there are still limitations and we are always mindful of what we miss from not being able to physically see, or examine a child or young person. We were forced to really expand our use of home-based sleep investigations, so a courier will take the equipment to the family’s house and our sleep physiologists put together a Youtube video teaching parents how to apply the various sensors. Parents manage really well, and of course they and their children prefer such studies to take place at home when possible.

Out of adversity has come some really good practice and it’s really important that we learn from examples where things have gone well, rather than reinvent the wheel. The Council for Disabled Children has published a series of resources and examples of good practice in response to Covid-19 on its website.

What advice would you give to parents of children struggling with disrupted sleep at this time?

During lockdown, the clock time drifted so there was this major physiological change with people going to bed and waking up much later. A lot of young people ended up living in a ‘New York time zone’ and some of them even got all the way to Los Angeles. It’s very difficult for the body physiologically when it’s out-of-sync with daylight and it’s also very hard when you suddenly have to go back to school and start getting up at a particular time. Dr Shreena Unadkat, clinical psychologist on the Evelina London sleep team, put together some really useful sleep advice with tips on everything from creating a routine to managing anxiety before bedtime.

What are the long-term implications for children with special needs and their families?

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) have consulted with children and young people and their members and they are saying that by redeploying professionals away from children’s services without consultation on such a wide scale, you’ve affected the health and wellbeing of children and their families and you have magnified the health inequalities that were already there. We need to restore and protect children’s services in the event of another wave because the harm to children outweighs the impact of coronavirus on children. For some children the damage will be irreversible; for example, where they are too anxious to go back to school or where the level of challenging behaviour has increased to such a magnitude that the family can’t cope or safeguarding concerns have been raised. These are things that never get forgotten and their impact will last a long, long time.

Selected background information and resources for children with special needs and their families in the context of Covid-19

1. Keeping children safe

Background

Children with disability are three times more likely to suffer abuse than non-disabled children. The NSPCC helpline received 1,066 contacts each month from April to July this year – up 53% on pre-lockdown average

Resources for parents

NSPCC

2. Special Educational Needs school provision during Covid-19

Background and resources

Independent Provider of Special Education Advice (IPSEA)

3. Home schooling children with SEND

UCL Institute of Education

4. Advice for children with learning difficulty and autistic spectrum disorders

National Autistic Society

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/coronavirus

Council for Disabled Children

5. Coping with challenging behaviour

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) Tier 4

https://bringingustogether.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CAMHS-Family-Survival-Guide.pdf

Challenging behaviour foundation

6. Sleep difficulties during Covid-19

Background

Survey by the Sleep Council: https://sleepcouncil.org.uk/latest-news/new-survey-reveals-covid-19s-impact-on-kids-bedtimes-and-time-on-devices/

Resources

Evelina London Children’s Sleep Medicine Department

Sleep tips for families

7. Financial challenges to families

Background

https://www.familyfund.org.uk/help-and-support-coronavirus

Resources

Application to Family Fund

https://www.familyfund.org.uk/FAQs/how-do-we-apply

8. Examples of innovation and good practice

The Council for Disabled Children has published a series of resources with learning and good practice on how children’s health, care and education services have adapted and innovated in response to Covid-19. Brief summaries of examples below.

9. Restoring children’s health services

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

Position Statement on Restoring children’s health services – Covid 19 and winter planning:

‘Without prompt attention to restore children’s health services and the workforce that delivers them, and to protect them from surge policies over the next few months, there is a real risk that current health inequalities will widen, vulnerable children will slip through the net, the burden of child ill-health and disease will grow and long term damage to workforce development and service innovation. Meeting children’s rights to access the healthcare they need cannot be deferred further.’

Insights from young people

Sixty young people from all four UK nations participated in focus groups led by RCPCH &Us in May and June 2020 – exploring healthcare experiences during lockdown.

https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-us-views-rcpch-us

Six young people aged 16-25 formed the COVID-19 Book Club. The club has been meeting for an hour each week to review studies and identify key themes. They had training on how to read studies, use collaboration software and understand the NHS recovery plan approach.

They give three recovery priorities for urgent action by NHS Trusts and health boards:

- Have child and youth accessible, friendly and relevant information about accessing health services and staying safe through the pandemic

- Increase access to mental health services to support children and young people impacted by the pandemic

- Create the best virtual health experience possible thinking about access, confidentiality, rapport and holistic care

https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-summaries-key-findings-children-young-peoples-views