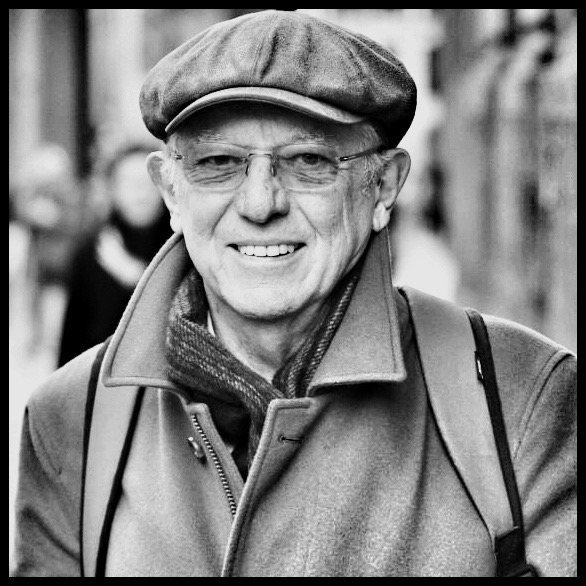

Children’s author and poet Michael Rosen contracted COVID-19 at the end of March and spent 48 days in intensive care, much of that time on a ventilator. We spoke to him about his ongoing recovery and the dangers of seeing older people as ‘collateral damage’

How is your health currently?

When I came home from hospital I could hardly walk upstairs, so I’ve been doing various forms of physio and walking as much as I can bear to do. I have lost some sight in my left eye and some hearing in my left ear so my balance is skew-whiff and I do get a bit of dizziness because of low blood pressure. I also have numbness in my toes which is a very strange feeling. When I first got home in June, people would say “Oh isn’t it great that you’ve recovered,” and I would say “I am recovering,” because to say I’ve recovered doesn’t quite engage with the drama of it.

At what point did you realise how serious your illness was?

I started getting ill around the 14th March. I had a temperature but I didn’t have a cough, I just felt lousy. Slowly, what started happening was not being able to breathe easily. About a fortnight into the illness I rang 111. The paramedic ran through my symptoms and said ‘I don’t think you’ve got Covid’. But then a neighbour who is a GP came round with an oximeter and I think the reading was 58, so that set alarm bells ringing. When I got to A&E they said that if I’d left it any longer I’d have faded and they wouldn’t have been able to get me back. I went into intensive care straight away and was there for 48 days.

How much of that period do you remember?

It’s all blurred. I’ve got vague sensations of wards and saying hello to nurses but of course I’ve got no memory of when I was in the induced coma. The two things I have that link me to that time are the scar from the tracheostomy and the patient diary that the nurses kept when I was in intensive care. They wrote me a letter every morning after caring for me at night. It’s a wonderful revelation of this strange person, who just so happens to be me, who was unconscious for seven weeks.

You’ve spoken about the physical after-effects of COVID-19, but what has been the emotional impact?

I keep having to come to terms with the fact that I’m a different person. I imagine it’s the same if you’ve had a car accident or a stroke. There is a point before and a point after and you have to come to terms with who you are now. When you’re in hospital, your body, and to a certain extent your mind, belongs to the hospital. The nurses and the doctors keep tabs on you, they fill a ledger full of information about your blood pressure, your bowel movements, what food and drink you’re eating. You surrender yourself to it. But when you come out they are no longer in charge. I still go to clinics but in between those times you have to own your frailty and vulnerability and that’s really difficult. For example, if I’m pushing the trolley round a supermarket and I bump into people because I’m a bit clumsy and then I think ‘Well, maybe I won’t go shopping,’ then I’m not owning it. It takes an intellectual effort to do it.

“There is a point before and a point after and you have to come to terms with who you are now.”

Michael Rosen

You’ve been quite vocal about the debilitating impact of ‘long Covid’. Do you feel anyone is listening?

For each one of my problems I see a different specialist but at no point have I been called in by the NHS and had someone say to me, ‘Just take us through what you were like before and what you are like now’. The government don’t take it seriously as an issue for public health. I’m a perfect sample. We could be summoned and used for research and we are not.

Having survived Covid, how has it felt to watch the second wave of this epidemic unfolding?

There is this horrible mismatch between what Boris Johnson and Matt Hancock say and what they do. So their rhetoric about the gravity of the illness is quite good and then there is this appalling mismanagement from the very beginning when they refused to take the WHO seriously, to the use of the private sector to do test and trace. If ever we wanted to expose the fallacy that the market can solve all problems, this terrible pandemic has told us this. They believe all of this stuff can be managed by people who are ‘managers’, whereas we have this incredible institution, the NHS, that has public health at its core and that was the instrument to have used. They get away with this absurd hyperbolic rhetoric – ‘world-class system’, ‘ramping it up’, ‘moonshot’ – and it is, to be blunt about it, bullshit and it feeds into conspiracy theories because people can spot that it’s bullshit.

You’ve spent a lot of time engaging with these conspiracy theorists on social media. Do you feel you have a duty to speak out?

Part of convalescing is keeping your brain going. It’s very easy and quite tempting to just sit on your tuchus and wallow in it. I find I need to correct myself and one way is to engage with the world. I have always felt that if you feel something strongly then you engage with it rather than hunker down in your corner and get miserable about it. So I am anti-miserabilist, I am full of hope and I believe that these things have to be engaged with at an intellectual and emotional level. The thing I’ve found is that when you say to conspiracy theorists ‘How does a virus spread?’, it all goes flaky. We are not dealing with a mystical cloud, we are not dealing with The Blob, a strange redcurrant jelly that engulfs people, we’re dealing with a virus and we have scientific knowledge of how viruses spread and multiply. Test, trace and isolate is the most rational way we know [to stop the spread], as well as wearing masks and social distancing.

Will your experience of COVID find its way into your writing?

When I was in the rehab hospital, I invented this character called Sticky McStick Stick. One day the physios came to see me and they said ‘Today you’re going to stand up,’ and I couldn’t and it was horrifying to me. But then, bit by bit, over three weeks they got me to walk and one of the transitions was the stick. So I have written a kids’ story about learning how to walk with Sticky McStick Stick and then rejecting him because I don’t need him any more and he sits by the door and watches me as I walk out. I invented this thing simply in order to humanise what I was doing. Who knows, maybe one day it will see the light of day.

I’ve also written a book which is coming out in March. It’s called ‘Many Different Kinds of Love’ and it’s a cycle of prose poems about getting ill and the struggle with recovery and it will have extracts from the nurses’ diaries and pictures by illustrator Chris Riddell.

What lessons do you hope that we as a society can learn from this pandemic?

The herd immunity idea the government had at the beginning may have been rejected but it is residual. There is a part of them that thinks ‘Well, if these people are dying in care homes and in hospitals, somehow the rest of the population is getting stronger.’ There is no evidence for that and there never was. It’s unethical anyway. At the end of the day you’re saying collateral damage is worth it; the over-70s are redundant, they are unproductive, so who cares anyway?

If I think about the old people in my life when I was young and what they were able to tell me, these are incredible ways to understand who we are and the world. It is actually a mirror of what we do with the under-15s. We make a sandwich where the first chunk is not very important and the last chunk is not very important, only the stuff in the middle matters. We have so reduced this matter of Covid to stats on risk that we don’t realise the way in which we are being corrupted by not seeing the totality of the human cycle. It’s a continuum and if you break the continuum you open the door to fascistic ideas about how some people are of more value than others.

Reasons to be cheerful: what’s making you happy right now?

Friday night takeaway. There are two fantastic takeaways here in Muswell Hill, so that’s making me happy. It’s wonderful being at home. I have offspring of various ages and it’s just wonderful being with them. That cycle of life thing is incredibly important and if you turn your back on it, it’s a very odd place. You feel very isolated and lost and in hospital that’s exactly what I was. I was isolated and lost without them and it’s lovely to be back.

Interview by Joanne O’Connor