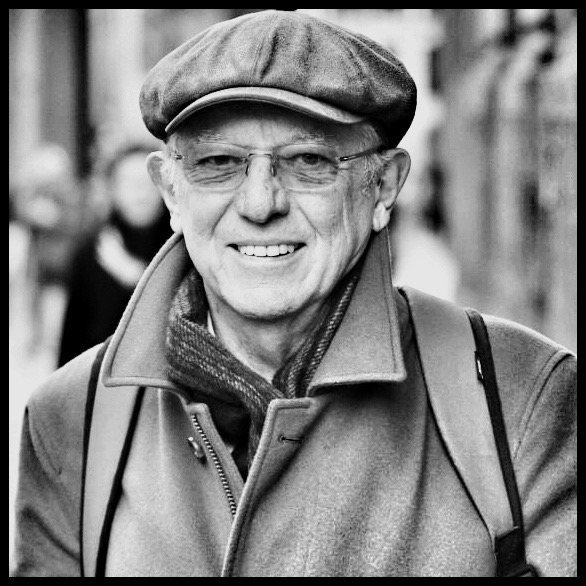

From apartheid to climate change, Sir David King has never shied away from confronting the big issues of the day. The former chief scientific adviser to the British government tells us why he believes Independent SAGE still has a vital role to play in tackling the pandemic

You grew up in South Africa under the apartheid regime. How did that inform your outlook?

It wasn’t possible at that time in South Africa to sit on the fence. You were either on one side or the other. My parents were adherents of apartheid, but my awakening came from our household chef, who was a Zulu. He was a wonderful story-teller and he began telling me the history of the Zulu people. I realised that the philosophy that I was brought up with, that black people were somehow inferior to the whites, was complete nonsense.

I went to university and one day I was talking to a black friend in the street. I lit his cigarette and a passer-by spat in my face. I became politicised at that point. I started working with the African National Congress. Their leader Nelson Mandela was picked up in 1962 after being on the run and I was picked up in ‘63 for assisting the movement. I was interrogated on the 10th floor of the famous central police building in Johannesburg – famous because people used to “spontaneously” jump out of the window to their death. I managed to negotiate my way out of South Africa, provided I never returned, that was the deal. So I got a one-way passport and came to London. I found Britain a very strange place. All the cafes had little cards advertising rooms for rent and every single one said ‘No blacks or Irish’. I thought I’d come to this wonderful liberal democracy.

Much of your work has been in the field of climate change. What set you on that path?

I’m a physical chemist and it is the interface between physics and chemistry that enables the modelling of climate change. I moved to Cambridge University in 1988 and in the department we had a group of people who’d been studying atmospheric chemistry, in particular the notion that CFCs being released into the atmosphere were responsible for the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica. So we worked with applied mathematicians and we modelled the ozone layer and were able to predict when the ozone hole would move. It was an incredibly powerful tool.

You were chief scientific adviser to Tony Blair. What was that like?

I was appointed in November 2000 and I was just getting my feet under the table when foot-and-mouth disease hit. The prime minister said ‘You’re in charge’ and he stood back and trusted me to go on television and radio to explain to the nation what we were doing and why. I formed a group of experts and the first thing we did was to model the epidemic. We showed that it was contact between animals on neighbouring farms that was spreading the disease. So once a case was confirmed, we culled all of the animals on the neighbouring farms to create a barrier to the spread. It was an enormous exercise and we had to get the army involved but within a few months we had it fully under control.

Once I had the prime minister’s trust, I could start talking to him about climate change and how little countries were doing in the face of this enormous crisis. We really started to push the agenda and Britain became the first country in the world to declare a long-term objective – an 80% reduction in carbon emissions by 2050.

At what point did you realise how serious this coronavirus pandemic was going to be?

When I was in government I set up an independent foresight process so that we could prepare for potential disasters. The biggest programme I ran was on infectious diseases. In 2006 we predicted a pandemic of this kind would happen before 2030. We said that because there are wild animals living in close proximity with people in many parts of the world, it is very likely that a chance mutation of a virus could lead to it becoming transmissible to humans and we calculated that within three months it would be in every country in the world. Under the Blair government we began the preparations. I had 320 experts working on the programme for two-and-a-half years. When the Coalition government came in in 2010 it was completely disrupted by the austerity measures. We were leading the world in preparing for just such a pandemic and we had all of the expertise, so when it became apparent that the government had no strategy, I was tearing my hair out.

The government already has its own advisory body, SAGE, to deal with emergencies. Why did you feel the need to set up your own version, Independent SAGE?

Because there is no transparency about what the government is doing, no open discussion whatsoever. At the start of the pandemic, the membership of SAGE and the minutes of its meetings were kept secret. During our first public meeting in May, the minutes of SAGE’s first six meetings and the list of members were published with a few redactions (Dominic Cummings’ name was removed). We embarrassed them into going public.

Once they’d gone public, why did you decide to keep going?

This country has already lost, unnecessarily, at least 46,000 lives as a result of unbelievably bad decision-making by the government. There was no understanding of the scale of this pandemic. The prime minister missed the first five meetings of the emergency Cobra committee. In February and March our hospitals were totally unprepared which is why doctors and nurses were dying. We gave up on Test and Trace in mid-March because the virus was out of hand. Then the government installed, without any competition, two private companies to carry out Test and Trace, neither of whom had any healthcare experience. Why would they do that in the middle of a pandemic? I believe there’s only one answer to that. If you are planning to privatise aspects of the National Health Service, [it makes sense to] push through those aspects of the agenda that would otherwise be difficult to push through, in the middle of a crisis.

A key part of Independent SAGE’s mission statement is making scientific expertise accessible to the public. Why is this so important?

First of all you have to bring together the right group of experts to give advice on how to handle an emergency. But the most important thing we do is to have open, public meetings. We produce draft reports before those meetings and then we change the reports based on the to and fro between the public and the experts. For the experts to hear what the public have got to say is absolutely critical and in that process you’re improving the advice you’re giving to the government. But there’s something else very important that you’re doing — you’re gaining the trust of the public and that’s what the government has failed to do completely.

How does it feel to see your advice being ignored by the government?

There was a point earlier in the year when we were saying, ‘Use the summer to manage this epidemic, try to get down to zero Covid, with a fully operative Find, Test, Trace & Isolate system’, because we knew that the winter months were going to be really difficult, and the advice was ignored and here we are going into a second wave. It is incredibly frustrating but we have to just carry on. In each case I’ve always told my colleagues ‘Don’t look backwards, we’ve got to take where we are today and give the best possible advice going forwards’.

If you could get Boris Johnson to act on one piece of advice what would it be?

The government keeps talking about the number of tests they are going to conduct, but testing is only one part of the process. The most important part is isolation and I’m not sure that they’ve understood this. The way to control an outbreak is to separate the people who are infected from the rest of the population, who can then get on with the business of keeping the economy going. There is this false dichotomy between the health of the nation and the health of the economy. You can’t have one without the other. And by failing to have a fully operative Find, Test, Trace, Isolate and Support system, we have been hit both ways.

It’s been six months since Independent SAGE started. How much longer will it continue?

That is a milestone that none of us are celebrating. We didn’t expect that we would still be needed after three months, but here we are. I’m extraordinarily proud of this group of people, who are all world experts in their fields. They all have tough day jobs and the work they have put into Independent SAGE has been quite remarkable and they are not paid a bean for it. But it’s a question of public responsibility. We will keep going until we feel that our advice has been taken and as a result the disease has stopped spreading. We will keep going until there is an end in sight and that end has to be a zero Covid Britain.